Как выбрать гостиницу для кошек

14 декабря, 2021

A schematic diagram is shown in Figure 2, depicting the main components of the ISAHP test rig. Table 1 lists the instrumentation and monitoring equipment used in the experiment, whose part numbers correspond to the schematic diagram.

|

Table 1 List of instrumentation used

|

The main components of the apparatus include: a nominal 1/3 HP single speed compressor, a thermostatic expansion valve, two flat plate counter-flow heat exchangers acting as the evaporator and condenser of the heat pump, a standard residential hot water tank (270 L), a variable speed pump and an auxiliary heater for simulating the solar collector heat input. R-134a was used as the working fluid for the heat pump cycle, and a 50 / 50% glycol/water solution by volume was used in the collector loop.

The collector loop operates in a similar fashion to that of a typical solar domestic water heating system. First, the glycol solution is pumped through the collector, or in this case the auxiliary heater, in a closed loop. The glycol solution absorbs energy through the “collector”, and a heat exchanger is used to extract the heat from the glycol, which acts as the evaporator of the heat pump loop. The R-134a superheated gas exits the evaporator and passes through the compressor, increasing in both pressure and temperature. The refrigerant then releases its heat and condenses through the natural convection heat exchanger, which delivers hot water to the storage tank. The R-134a liquid then passes through the thermostatic expansion valve, reducing its pressure before re-entering the evaporator.

To investigate the influence of the collector costs on the cost/benefit ratio and the dimensioning of the system, the specific collector price was gradually reduced to 70% of the base case. Such a reduction could be realistic with improved materials and/or production processes. All other parameters match the base case. Figure 3 (a) shows that the less expensive collectors lead to higher primary energy saving, due primarily to an enlargement of the absolute collector area in the optimal system configuration. In opposition to the enlargement of collector area the storage device capacity almost stays constant within the examined range of collector costs, which means that the specific storage volume decreases. Selected results of the best configurations for the respective collector costs are listed in Table 1.

The feasibility and sensitivity analysis for Case 1 with pellets and oil as fuel are shown in fig 3. With today’s pellet prices a feasible payback period cannot be found during the plants estimated lifetime. With annual pellet price increases of between 5-10% the feasible payback periods start to come within

|

the range of the estimated lifetime. With today’s oil prices a feasible payback period can be found in Sweden but not in Finland, where an annual oil price increases of between 2-5% would be needed.

Two solar glazed panels heat up the heat carrier fluid of the solar loop. The absorbing total surface of the two collectors is 4 m[10] [11]. They are facing south (azimuth angle 0°) and have 45° with the ground. Neither roof integration nor shadows are considered. Collector parameters are: optical coefficient B = 0.81, firs order thermal coefficient k1 = 3.61W/m2K and second order thermal coefficient k2 = 0.0045 W/m2K2 . Stagnation temperature is 215°C’.

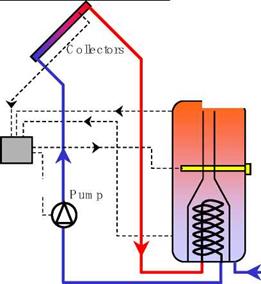

A 300 liters tank is used to storage the solar energy (figure 1). At the bottom of the storage tank an integrated heat exchanger supplies solar energy recovered by the panels. This exchanger is installed inside a stratifier high as 90% of the tank. The tank has also an auxiliary electric heater allowed to run between 22.00 and 6.00 if the upper volume didn’t reached the set-up temperature2. The upper volume heated by the auxiliary heater is 100 liters. No stratification is possible in the volume above the heater when in operation [1].

Tap hot water is delivered at 50°C by a thermostatic mixing valve. This one add cold water to the hot water from the tank.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Layout of a domestic hot water solar heaters (HWSH).

A classic control device is an electronic box able to take two decisions:

• To run or stop the pump of the solar loop depending on the temperatures registered in the collector and at the bottom of the tank;

The new control device is able to decide also the set-up temperature of the auxiliary heater depending on the needs and on the weather forecast [2, 3].

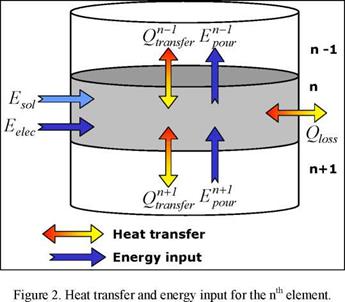

Presented model is a finite difference one with nodal discretisation, and is based on the mass and energy balance. The simulations are carried on by dividing the tank in many isothermal elements or slices, with equal volumes. For each element we take into account the next heat transfers and energy interactions (figure 2):

• Heat lost to environment,

• Heat exchange with n-1 element,

• Heat exchange with n+1 element,

• Energy input from the electrical heater,

• Energy input from the solar exchanger,

• Energy input from the n+1 element when hot water is poured,

• Energy output to n-1 element when hot water is poured.

The most important barriers for a broad application of small scale combined solar heating and cooling systems — further on called Solar Combi+ — and the solutions proposed by the project to overcome them are as follows:

1. Combined solar heating and cooling needs specialised design in order to make the single components play together optimally. So far every single system is designed from scratch. This (i) leads to a financial effort, which is not feasible for small applications, as design costs become prohibitively high in relation to hardware costs and (ii) often might overstrain the solar thermal installer, who would in most cases be the provider of the system to the end-user. Today there are no design guidelines for small scale systems and very few, yet not validated, package solutions on the market.

Virtual case studies will overcome this gap: Promising configurations will be identified, simulated for different typical conditions (i. e. utilization, climate, building type) and finally economically and ecologically rated. Out of the large number of virtual case studies, a small number of standard system configurations, which work best under different conditions are identified. Based on these, small scale sorption chiller and solar thermal industry will be able to provide consistent package solutions. These will enable planers and independent craftsmen to install reliable systems.

2. Small scale sorption chillers are expensive as production volumes are currently low.

The economical and ecological rating of the above described virtual case studies will allow identifying the most promising markets, where systems are yet at the edge of economical breakeven point or beyond, compared to traditional solutions. Accordingly tailored promotion and market strategies will considerably trigger the application of the technology. Following economies of scale will make small scale combined solar heating & cooling less expensive and thus viable in a broader range of applications and climates.

3. Small scale combined solar heating & cooling is not well known by traditional small scale solar thermal installers, planners, architects and potential clients.

Tailored dissemination plans include among other measures the training of solar thermal installers, targeted presentations to professionals, information of the public in most promising regions as well as advice to policy makers and promotion of pilot plant installation to public authorities.

The STS consists of 32 solar collectors with unit aperture area of 1.86 m2. The solar field is divided into 8 groups of 4 collectors oriented both at 27° (4 groups) and -63° (4 groups) azimuths, given architectural and space constrains. The tilt angle is 35°, optimized for the building latitude.

The effect of the decoupled orientation from south was studied on a daily basis and found never to exceed a 12% penalty (regarding an optimal south facing orientation) in monthly average (value for December, the less favourable month, being for example 8% in March, 1.35% in April, 0.87% in May and 0.16% in June).

The feeding of the collector batteries facing east and west is independent, thus using two separate lines starting in the pumping group (located in the basement, -1 floor).

After passing the two parallel collector fields, each one composed with 4 parallel groups of 4 collectors in series, the thermal fluid shares the same pipe which in turn feeds 5 vertical lines going to the independent building sectors feeding the individual storage tank located in each apartment.

Along its course, each line feeds 4 dwellings, until the technical room is reached. At the end of these lines there are flow meters and regulation valves to assure the hydraulic balance.

The heat exchange from the primary system to the secondary is done via a heat exchanger inside the storage tank located inside each dwelling. When the temperature inside the individual tanks, is higher than temperature of the primary water circuit, a three way valve was projected to avoid the heat transfer in the wrong direction.

The system has 4 pumps, 2 for each azimuthal group of collectors working in turns, so that the pumps can be repaired, if needed, without having to stop the system.

Upstream from the pumping group there is also the safety group, consisting in expansion vessel and a pressure safety valve, for each feeding line to the collectors.

The circuit includes also an energy count system, consisting of two temperature probes and a flow meter, that send information to the central which has a differential controller and calculates the energy delivered by the solar system. The "hot probe" is inserted in the totalizing pipe downstream after the two collector fields. The "cold probe" is placed just upstream of the pumping group.

Fig.1 is a schematic representation of the primary circuit.

|

Fig. 1. Schematic draw of this STSs primary circuit. |

To compare the dynamic operation of the ISAHP system with the steady-state computer model [4], a 6 hour test with varying glycol temperature was performed. Due to stratification, the temperature at the bottom of the tank remained constant throughout the test providing a constant input temperature for the condenser on the water side. A description of the experiments performed is given below.

1.2. Test Sequence

For the simulated solar day test, the heat out of the auxiliary heater was varied in a sinusoidal profile similar to that occurring on a clear sunny day. The following procedure was followed for the test:

• Prior to testing the storage tank was filled with water at mains temperature to ensure that the entire tank was at constant temperature.

• During this time the collector loop fluid was brought to the desired initial temperature for the test, and the loop flow rate was set to 77 kg/h (0.021 kg/s). This flow rate was used in the simulations previously undertaken, and is based on recommendations by Fanney and Klein [14].

• The data acquisition (DA) system was initialized with the compressor running, and the program delivering the power profile to the heaters was commenced. Data was recorded every 5 seconds for the duration of the experiment.

• COP and natural convection flow rate were then calculated based on the collected data.

For investigating the effect of the thermal behaviour of the solar collector on the entire system the optimisation process was executed with five different collector efficiency curves representing typical collectors available on the market [4], see Table 2.

|

collector |

П0 [-] |

a1 [W/(m2K)] |

a2 [W/(m2K2)] |

|

I |

0.825 |

3 |

0.013 |

|

II |

0.815 |

3.25 |

0.014 |

|

base case (bc) |

0.8 |

3.5 |

0.015 |

|

III |

0.78 |

3.75 |

0.0175 |

|

IV |

0.75 |

4 |

0.02 |

|

Table 2. Simulated flat-plate solar collectors |

![image250 Подпись: AT [K] Fig. 4. Efficiency curves of the solar collectors.](/img/1155/image250.gif) |

Figure 3 (b) illustrates that the respective optimal system configurations move towards higher primary energy savings while the additional costs become smaller when improving the solar collector. Table 1 shows that the dimensions of both, solar collector area and storage device capacity, almost stay constant. A high efficiency collector does not induce a bigger storage capacity to reach the best cost/benefit ratio.

The MaxLean system concept was developed to be operated with a non-pressurized and thus inexpensive storage tank. As the price of the base cases storage tank reflects pressurized storages currently on the market, the influence of reduced storage cost has been investigated, ranging down to 60 % of the base case storage costs. Presuming an enlargement of the system dimensions due to lower storage costs, Figure 3 (c) shows however that, by reducing the cost of storage tank, the respective minimum of the objective function gets smaller owing to a reduction of the additional cost while the underlying dimensioning parameters do not change (see Table 1). This trend persists down to 70 % of the original price, when the optimal storage device capacity gets slightly bigger while the collector area decreases. The two effects of shifting towards lower additional costs and the flattening of the optimisation curves due to a greater cost reduction with larger systems are leading to points of intersection of the line tangentially meeting the curve with approximately the same primary energy savings.

The feasibility and sensitivity analysis for Case 2 with pellets and oil as fuel are shown in fig 4. It can be concluded that with today’s pellet prices a feasible payback period cannot be found during the plants estimated lifetime. With annual pellet price increases of between 5-10% the feasible payback periods start to be shorter than the estimated plant lifetime. With oil as fuel feasible payback periods shorter than the estimated plant lifetime can be found already with both countries’ current prices.

The total thermal resistance of the vertical wall of the tank is:

|

|

|

|

![]() The convection coefficient in air hair

The convection coefficient in air hair

Nuair = 0 if Ra < 104

Nuair = 0.59 ■ Rar0f if 104 < Ra < 109

Nuair = 0.13 ■ Ra033 elsewhere

The convection coefficient in water hwater is obtained from the next relationship:

г -|2

Supplementary losses appear for the first and the last element, at the top and the bottom of the tank. Different relationships are employed for these two horizontal surfaces in contact with ambient air depending on the temperature gradient. If heat is recuperated from the environment next correlations are computed:

Nuair = 0 if Ra < 104

Nuair = 0.54 • Ra0 25 if 104 < Ra < 109 (4)

Nuair = 0.54 • Ra0 33 elsewhere

And, if heat is lost to the environment, the correlations are:

![]() Nuair = 0if Ra < 104 Nuair = 0.27 • Ra0 25 elsewhere

Nuair = 0if Ra < 104 Nuair = 0.27 • Ra0 25 elsewhere