Как выбрать гостиницу для кошек

14 декабря, 2021

Thin films of Tin Iodide (Snl2), Manganese Bromide (MnBr2), Lead bromide (PbBr2), Lead Iodide (Pbl2) Lead Sulphide (PbS) and Silver Sulphide (Ag2S) were grown on glass slides using the Chemical Bath Deposition (CBD) method also called the Solution Growth Technique (SGT) [2, 9, 10]. The surface structures of the films were obtained by taking photomicrographs of the films with a Leitz Labourlux Photomicroscope. The photomicrographs were then used to study the surface microstructure of the films by applying the Jeffries (Planetric) measurements with a circle 79.8mm in diameter drawn on a transparency. This drawn circle was placed on each photomicrograph one after the other to count the number of grains falling within the circle N1 and those intersecting the circle N2. The values of N1 and N2 were then used to compute the grain size parameters by applying equations 6 to 15, while the porosity factors were obtained with equations 16 and 17. Only films whose thickness is such that the individual grains are visible and identifiable on the photomicrographs were used for this study [2, 4].

After taking the photomicrographs of the films the coated slides were then put in the transmission beam path of a Pye-Unicam (Sp 1000) spectrophotometer to obtain the spectral transmittance curves of the films, with a similar but blank glass slide in the reference beam path of the spectrophotometer.

Plates 1 = 6 show the photomicrographs of the films mentioned above respectively, while table 1 shows the computed grain size parameters and porosity factors for the films. Figs 1 — 3 shows the spectral transmittance curves of the films.

|

|

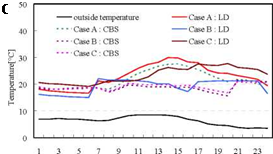

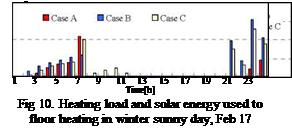

Fig.9 shows the room temperatures of the living room (LD) and the south children’s room (CBS) in February 17. The room temperature of LD in Case A (no adjacent houses) rose to about 30°C by the incident solar radiation from the south window in the daytime. The room temperature of LD in Case B (adjacent houses) was 20°C of preset temperature in the daytime. The room temperature of LD in Case C (adjacent houses and active solar heating system) was about 23°C to midnight. Fig.10 shows heating load and solar energy used to floor heating in winter sunny day (February 17). Daily total heating loads for Case A, B and C were 2.75kWh, 6.30kWh and 5.97kWh, respectively. Daily total heating loads for Case B and C increased by 2.3 times and 2.1 times compared with the Case A, respectively. Daily total solar energy used to floor heating in

|

|

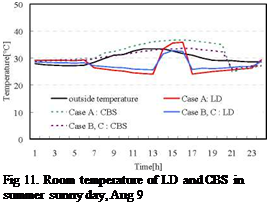

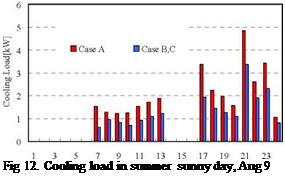

Fig.11 shows the room temperatures of LD and CBS in August 9. The room temperature of LD in 15:00 for Case A and Case B, C were 35.5°C and 32.8 °C, respectively. The room temperature of CBS in Case A was high about 3.3°C at the maximum compared with it in Case B and C at the time of non-air-conditioning. Fig.12 shows cooling load in summer sunny day (August 9). Daily total cooling loads for Case A and Case B, C were 31.57kWh and 20.55kWh, respectively. Daily total cooling load for the adjacent Cases B and C reduced by 38% against the no adjacent Case A.

As flat roofs;

• offer flexible possibilities for proper orientation and inclination,

• has less possibility of shadowing,

• mostly has large surface area,

• has proper conditions for easy maintenance, repair and access,

• allows to economical solutions,

they are the building surfaces where the system usage and the problem is mostly seen. When forming individual or central systems on flat roofs, the sufficiency of the roof for system application (form, dimension, building envelope and structure characteristics, etc.) and efficacy of the roof on architectural expression are the important issues that have to be apprehended and associated. From this point of view, for adequate usage of solar hot water systems on roofs, the basic topic of a design process that can be fallowed can be organized like,

1. Detailed analysis of the roof;

• Solar access

• orientation,

• Shadowing (roof elements, environmental effects, etc.)

• Physical properties,

• Form and size (dimensions);

• Specifications of roof components, (chimneys, stairs, top covers, windows, etc.

• Technical properties,

• structure,

• envelope section

• Architecture,

• effectiveness in architecture expression,

• association with the whole of the building

• aesthetic perception

2. Decision on the system form to be used on roof;

• Invisible, building component / central, individual, etc.

3. Calculations of efficiency, sizing the system and defining the system components,

4. Decision on the collector and tank areas;

5. Formation (designing) of these areas

• Ensuring the harmony with the building; by considering the form / size, color / pattern properties and achive completeness and integrity,

6. Ensuring the reliability of the system

• Good quality of infrastructure and the installations and correlation with the construction

• Technically and technologically meeting the all quality and quantity needs.

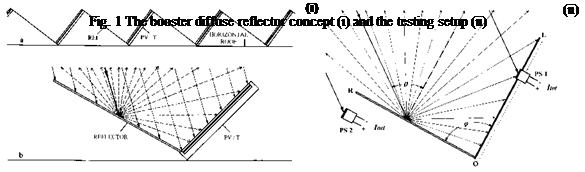

The simplest mode for concentrating photovoltaics is the combination of plain PV modules with flat diffuse reflectors. The increase of the energy output of PV modules can be achieved by using flat diffuse reflectors as boosters to the PV modules, which give an almost uniform distribution of the reflected solar radiation on PV surface. In horizontal roof installations (Fig. 1-i), the PV modules are usually placed in parallel rows, with a distance between them to avoid shading. A fraction of the incoming solar radiation on the horizontal PV installation is not used by PV modules from Spring to Autumn, as solar rays are striking the free horizontal surface between the parallel PV rows. This fraction of radiation could be partially used by the PV modules if booster

|

diffuse reflectors are placed between the parallel PV rows and increase the solar radiation on PV surface. The diffuse booster reflectors achieve a smoother distribution of the additional solar radiation on PV surface, which is almost uniform for some reflector-PV module geometries [20]. The additional solar input on the surface of PV modules is lower than that of specular reflectors, but diffuse reflectors are cheaper and can be combined easily with typical size PV modules.

|

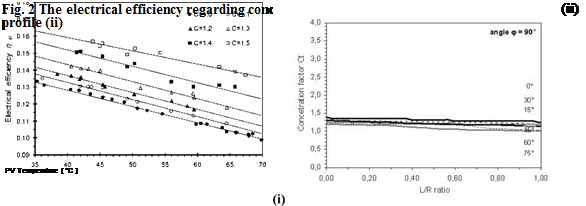

Photovoltaic modules of pc-Si type with aluminum diffuse reflector were tested with variable percentage of the additional solar radiation from the diffuse reflector, with respect to its electrical efficiency as a function of the PV module temperature. The efficiency Пеі was calculated for C=1 to C=1.5 (with step 0.1), adjusting properly the device for the achievement of the corresponding values of total solar radiation on PV module surface during noon. To keep stable the PV temperature TPV during the experiments, water was circulated through a heat exchanger of a thermal unit mounted on PV rear surface. In Fig. 2-i the results from these tests are presented.

To measure the effective concentration factor Ct of the diffuse reflector, angles ф of 90° and 120° between the reflector and the plane of the PV module were selected and the distribution of solar radiation on the PV surface as function of the angle of incidence в was derived. The angle ф=90° gives satisfactory results, while ф=120° is an upper limit of effective angles. A photosensor of small c-Si PV cell (1 cm2) was used to measure the net Inet and the total Itot incident solar radiation on the plane of PV module. In Fig. 1-ii the device for the measurement of the concentration factor Ct for variable values of the ratio L/R is shown. L is the PV module width [OL] and R the reflector width [OR] respectively. In practical applications L/R<1 should be considered. In the experiments a flat aluminium sheet with satisfactory diffuse reflection profile was used (Fig. 2-ii).

There is no official definition of specific goals and figures for low energy buildings. Some attempts have been made to define a low-energy building. In general, it refers to a building built according to special design criteria aimed at minimizing the building’s operating energy [11].

500

![]() 450

450

400

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

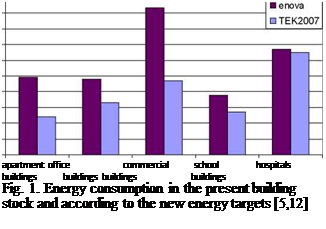

Figure 1 gives an overview of the estimated energy consumption of the building stock and the energy target for aggregate net energy demand for different building types in kWh/(m2 a) [5,12]. It shows that the new building regulation requires a drastic reduction in energy consumption (i. e. 50% in commercial buildings and 31% in office buildings). In Germany, the ‘lean building’ has been defined with specific primary energy consumption of 100 kWh/(m2a) [14]. The new energy labelling system will help to categorize the levels of energy use in buildings [15].

The available roof area is the sum of the areas that are suitable to install PV panels. These are the areas where incident solar irradiation is high. Since tall buildings are very rare in Portugal and neighboring buildings are usually far from school buildings their shading effect was neglected. In pavilion schools (flat roofs) the available area is equal to the total roof area because the PV panels

The perspirable building has a perspiration function by simulating the mechanism of concentration gradient, osmotic pressure, capillarity, mechanical energy and electric potential difference controlling perspirable action in a human body. The perspiration function in the building manifests itself with the construction of perspirable roof and wall (window) using thermo-sensitive hydrogel as a new material. The thermo-sensitive hydrogel is absorption/desorption resin with thermal reversibility; water is absorbed below a specific sense temperature and desorbed over the temperature, like perspiration in a human body. It is the evaporative cooling performed not by water sprinkling onto the roof but by the autonomous perspirable function of the wall.

|

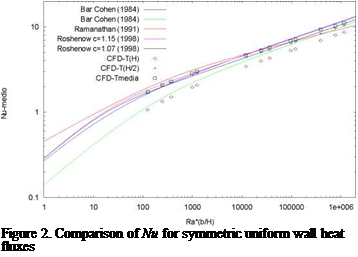

A wide number of simulations have been carried out (381); some of them have been used to validate the CFD model and the numerical assumptions with experimental results and previous authors. In the case of laminar situations, maximum deviations of 10 % have been obtained in the prediction of average Nusselt numbers and mass flow rate. In figure 2, a comparison between the numerical values of Nu and the mathematical expressions of different authors is showed [1,13,14].

1.1. New correlations for Nu and mass flow rates

Using the CFD simulations and applying a non linear regression based on iterative estimation algorithms (through the SPSS software) different correlations for the cases with asymmetric isofluxes have been obtained. In the case of the Nusselt numbers, the new correlations are based on the expressions of Bar-Cohen and Roshenow [1], but including the effect of the asymmetry (qwc / qwh), being qwc and qwh, the hot and cold wall isofluxes respectively:

Where: Nuh ,fw is the average Nusselt number for the hot wall; Nuc t is the average Nusselt number

for the cold wall. In the case of the mass flow rate, a new correlation for the friction factor has been obtained:

A comparison of these three correlations with the numerically calculated results has shown deviations lower than 6 %. However, some refinements in the equation 2 for situations with low Rayleigh numbers and in equation 3 for high asymmetric cases will be carried in the next future.

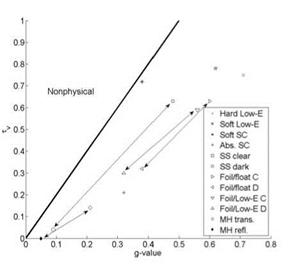

There are a large number of coated and uncoated glass panes available on the market, and all of these can be combined into numerous different window combinations. To help customers select suitable windows among this almost infinite number of glazing combinations, the International Glazing Data Base (IGDB) has been set up by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California [12]. The database contains glazing products manufactured by most major glass manufacturers in the world, and their main optical properties are provided, usually together with reflectance and transmittance spectra. It is a complex task to choose the most suitable window for a certain building and location out of all these products. The important parameters for the function of the window vary within wide limits, and if we for example consider the U-value and the g-value, we can see in Fig. 1, that windows with many different values of these parameters are available. Each point in the diagram represents a window made up from two panes found in the IGDB. The figure only includes a small selection of double glazed configurations air filled insulated glazing units. Triple glazed configurations with argon-fill would extend the graph down to U-values of around 0.6 W/m2K. Depending on the function of the window and the type of building, orientation and climate, different combinations of high or low U — and g-values would be the best choice. For optimum performance in a certain situation we may want to look for a window close to one of the corners in the graph. Often a compromise has to be selected since summer and winter may require quite different properties for optimum performance.

|

з

1.4 1.2 |

10 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9

10 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9

g-value

Fig. 1. U-value vs. g-value for over two thousand Fig. 2. Visible transmittance vs. g-value for twelve double pane windows. double pane windows.

These considerations lead to the conclusion that we often would want windows with variable optical and thermal properties depending on the time of year, time of day or weather. The electrochromic coatings mentioned in the introduction bring us a few steps towards this situation. Existing products on the market or prototypes made up in the laboratory show that we can identify window products with variable optical properties. A few examples are shown in Fig. 2 where the product specifications have been plotted in a graph with tv versus g-value. Table 1 gives a brief description of the double glazed windows presented in this graph. This type of graph is mainly useful for solar control glazing, for which both a low g-value is desired to prevent over-heating and a low Tv-value is desired to prevent glare. The problem is that we also want high tv for the daylighting and visual contact with the surroundings. Thus, the switchable electrochromic glazing could be the ideal solution. In the graph we can see that the shown optical properties can be varied within quite wide limits, which makes it possible to optimize the performance for different weather conditions and according to the needs of the occupants. The non-physical area in the graph is due to the fact that around 50% of the solar radiation is visible light.

|

Table 1. Description of pane configuration used for double pane windows in Fig. 2

|

3. Method

3.2. Energy simulations in WinSel

The energy simulations were performed using WinSel, a simulation tool developed at Uppsala University [7,8]. The program was designed as a window selection and energy rating tool, hence the acronym WinSel. Hourly climate data of direct and diffuse radiation and temperature are used for hour-by-hour calculations of the annual energy balance. Window in-data are the total solar energy transmittance (g-value), the thermal transmittance (U-value), and parameters controlling the

angular dependence of the g-value. The building input data are limited to the thermal mass dependant time-constant and the balance temperature. The balance temperature is defined as the outdoor temperature when neither cooling nor heating is required to maintain the set indoor temperature. Consequently, the heating season is defined as all hours of the year when the outside temperature is lower than the balance temperature. The cooling season is defined with a temperature swing allowing the indoor temperature to increase to a value above the set indoor temperature before any cooling is considered.

The notion of exergy, also called availability, was introduced at the end 19th century by Georges Gouy. This concept merge both the first and second law of thermodynamics and then allow to take into account the amount of energy transfer during a process but also the quality of this energy transfer. The exergy could be physically defined as the maximum mechanical work that a system could provide during a transformation between a thermodynamic state and a reference state. This means if a system is in thermodynamic non-equilibrium compared to the ambiance, the maximum work it could provide to reach back ambient conditions is the exergy; the difference between the achieved work and the exergy between the two states being the losses or irreversibilities. In this case, the exergy is positive; a negative exergy meaning that work should be provided to the system to reach back the reference state. Exergy is a state function and is defined as

e = (h — h°)-T0 (s — s0) (9

de = dh — T0ds

the indexes "0" referring to the reference state. For driving cycles, the reference state is conventionally the standard conditions, T0 = 15°C, P0 = 1bar. In addition, in the case of vapor evolving in a closed system, the only equilibrium condition compared to the ambient is the temperature condition. Indeed at equilibrium the system will reach the same temperature than the

ambient. However the equilibrium pressure will be the saturation pressure. For such system the reference state is T0 = 15°C, P0 = Psat (T0 ) . For driving cycle this definition is convenient since

this reference temperature is closed to the cold source temperature of the cycle, providing a very small or almost zero exergy loss at the condenser. Indeed, even though a large amount of energy is lost to the ambient, the quality of this energy is quite poor.

In our trithermal air-conditioning cycle, the hot source is the hot water previously heated up by solar collectors. The useful effect occurs at the cold source e. g. the water to cool down (for room air-conditioning) while the sum of those two previous heat quantity is discharged to the ambient through the condenser which is the medium temperature source of the cycle. Similarly to what happens at the condenser for a driving cycle, this significant amount of energy has a poor quality in regards to the targeted effect (cool down compared to ambient). Consequently, an almost zero exergy loss should be requested at this component. In addition the useful effect at evaporator occurs close to 15°C (tow — tiw «12 -18) providing an almost zero exergy variation for cooled

water and almost 100% of losses at the evaporator. All these conditions show that the usual reference state for driving cycles is not suited to air-conditioning cycles. Consequently in this study the reference temperature will be the ambient temperature Tciw at the condenser side. For the refrigeration cycle, the reference pressure will be the saturation pressure at T0 for propane and for secondary cycles (generator, condenser, evaporator) it is the atmospheric pressure (P0 = 1bar).

From an energy point of view the quality of a compression air-conditioning cycle is determined by the global COP as

COP = Qe (10)

comp, global p

1 comp, a

For an ejector based air-conditioning cycle this global COP would then be:

COP, c„b,, = P &+ Q (II)

pump, a sol

With subscript “a” for “absorbed” and Qsol the useful thermal power received by collectors.

However it could be convenient to define cycle based COP in order to eliminate mechanical efficiencies of components which may change significantly according the technology, power, etc…, and also to eliminate the source of heat supply. Indeed, in the proposed cycle solar collector are used to heat up the water but other low grade energy sources could be used to provide this energy; and in this case the way of calculating the energy transfer between the water and a source would be different or it would use very different efficiencies. Consequently to be more general, the concept of cycle based COP is used in this analysis:

COPcomp = PQ^ (12)

comp

|

|||

|

|

||

|

|||

These purely energy criteria are not satisfactory to make a relevant comparison between both systems. Indeed for the compression system the energy input is purely mechanical and then this energy is actually a pure exergy, while the ejector system uses primarily thermal energy which does not have the same exergetic value than a mechanical energy. Therefore, in order to compare

both systems on the same objective basis, these COP should be turned into exergetic COP. For the compression system it is obvious because the compression power is purely exergy while for the ejector system Qw should be replaced by its exergy equivalent. An easy way of calculating this exergetic value would be to consider the secondary water as a perfect source delivering a thermal power Qwg at a certain temperature T and using the Carnot factor:

This method may also be used for condenser or evaporator and was used in literature [3]. However this provides not accurate results since the water temperature varies and then it is not a perfect source. In this way the real exergy flux through the generator is used since all secondary cycles (generator, evaporator, condenser) are fully computed in this work:

ew, g = mgw (ew,0 — ew,, )g +amgw (ew,0 — ew,, LP (15)

In addition as proposed in literature an exergetic value of Qe should be used in exergetic COP.

This definition is not used in the current analysis because the useful effect is not mechanical such as in driving cycles/machines but thermal. Such definitions are not relevant since the exergetic value of Qe is very low giving even lower COP and not relevant to compare with classical COP. Consequently it is proposed to compare COP for a same thermal effect at evaporator:

Results are presented in the table 2. It is seen that in an energetic point of view, the ratio between the COP obtained for a conventional compression system and the EACS is very high (18.42 to 29.9). But the ratio of exergetic COP is noticeably lower, with values of around 3.4 to 5.7. It is thus important to highlight that both kind of systems are more comparable in an exergetic point of view, and this definition points out the valorization of the low grade energy. For Tciw=28.4°C, COPej and

COPe undergo the same increase of 6.6 % when the subcooler is used. For Tciw=29°C, COPej

and COPe decrease both of 29%. Note that a comparison between two cases at different Tciw is not

possible in an exergetic point of view, because the chosen reference T0 used for the exergetic analysis is equal to Tciw and thus varies with the considered case.

|

Table 2: COP and COPex comparison of the EACS and vapor compression cycle, for a=0.13, with and without the use of the subcooler. * denotes a working with regenerator using (P>0)

|

3. Conclusion

A detailed rating modeling of the EACS was presented. It was seen that the subcooler can have either beneficial or harmful effect on performances. The advantage of using of a regulator is clearly demonstrated. Moreover, reducing the system performances to an optimization of the ejector entrainment ratio is not judicious. The whole cycle must be taken into account. Finally, a first step of the exergy analysis of the EACS emphasized the more relevant comparison with a conventional vapor compression system. A more detailed exergetic study is in progress to determine the distribution of irreversibilities in the cycle and its variation with different parameters.

References

[1] W. Pridasawas and P. Lundqvist, A year-round dynamic simulation of a solar-driven ejector refrigeration system with iso-butane as a refrigerant, International Journal of Refrigeration, Vol. 30, 2007, 840-850.

[2] G. K. Alexis, E. K. Karayiannis, A solar ejector cooling system using refrigerant r134a in the Athens area, Renewable Energy, Vol. 30, 2005,1457-1469.

[3] W. Pridasawas and P. Lundqvist, An exergy analysis of a solar-driven ejector refrigeration system, Solar Energy, Vol. 76, 2003, 369-379.

[4] A. Hemidi, Y. Bartosiewicz, J. M. Seynhaeve, Ejector air-conditioning system: cycle modeling, and two — phase aspects, Heat 2008 conference, Vol. 2, 421-428.

[5] A. Hemidi, Y. Bartosiewicz, J. M. Seynhaeve, Modeling of an ejector air-conditioning system: sizing and rating tools, IIR conference, 2008.