Как выбрать гостиницу для кошек

14 декабря, 2021

According to the standard ISO 9459-2, test procedures for characterizing the performance of solar domestic water heating systems operated without auxiliary boosting are established. A “black box” approach is adopted which involves no assumptions about the type of system under test; the procedures are therefore suitable for testing all types of systems, including forced circulation, thermosiphon, freon-charged and integrated collector-storage systems. The test system is applicable only to systems of 0.6 m3 of solar storage capacity or less.

|

Fig.1. ISO9459-2 test system principal flowchart |

The structure and flow charts of solar water heating test system is shown in the figure 1. The main components of test system include units as shown below, constant temperature tank, return tank, water heaters, cooling systems, water distributor, water collector, pumps, solenoid valves and other components. The instrumentations coincided with measurement requirements of ISO 9459-2 contain pyranometers, diffuse pyranometers, anemometers, flowmeters, PT-100 thermal resistance and data recorders. Pipe system in test system of solenoid valves and non return valves to control the direction of flow can be achieved with the open-cycle and closed cycle. And so, solar water heating test system can separately test daily system performance, the degree of mixing in the storage vessel during drawoff and the storage tank heat losses.

After repeated testing determined in design, now the test system is completed. Solar water heating test system is presented in Figure 2 as follows.

|

Fig.2. Photo of the test system |

In Portugal 1/5 of buildings are occupied during only a part of the year [4]. Many cases of emigrant people and second house for holidays are example of this. In these cases, there are not regular consumptions and applying the regulations can originate a potential for excessive energy production. In some summer occupied homes the solar collector mounting tilt angle should be lower, above 35°, to maximize gains, maintaining the minimal area required [7]. Even another problem can be faced. The number of householders can vary widely. On this case, the system is over dimensioned and the equipment can not be cost-effective solution.

5.3 The integration on building architecture and construction

The collector’s building integration is a new challenge for architects. It known that the recommendable optimal panel tilt angle is the local latitude angle plus ± 5 °C [7]. Portuguese continental territory has latitude angles between 36° and 42°. In horizontal roofs this angle it should be guaranteed by an independent structure. On pitched roofs the better choice was to follow the roof tilt angle but it should be south oriented and not always is like that. If this is the case, is necessary to mount an independent structure for the panels using the calculations tilt angle and

south-orientation. The result is a strong and negative visual impact on building architecture. In large panel areas, this solution even can result in more mounting panel area because some panels can more easily obstruct others. Some facade elements near the roof can make a good role on disguising this type of installation. If the roof is E and/or W oriented, the panels tilt angle need to be reduced to 25°C to guarantee not more than 5% of decrease in energy captured [7]. On this case, it could be difficult to use the roof tilt angle. But if the roof is south-oriented the decrease of energy captured by not using the optimal angle is insignificant comparing with the benefits in cost, panel safety to wind and building aesthetic [7]. The most current tilt angle roofs in Portuguese buildings vary between 20° and 50°. Are these angles proper to be adopted and still get solar collector energy? It were made simulations using the software Solterm (version 5.0) for a three bedrooms autonomous zone (4 householders/4m2 of minimal SCA by regulations) and using a range of tilt angles between 20°-50° . Nine different Portuguese localities representing the nine continental climatic zones (locality — climatic zone) were selected: Agueda — I1V1, Albufeira — I1V2, Alandroal — I1V3, Alcobaqa — I2V1, Alcanena — I2V2, Castelo de Vide — I2V3, Celorico da Beira — I3V1, Braganqa — I3V2 e Mirandela — I3V3. The other fixed parameters were:, a south oriented panel; a water storage tank with 200 l of capacity, a gas boiler and the solar collector standard defined by ADENE (chapter 3). It was observed from the Esolar values that for a same autonomous zone: the south localities are better to capture solar energy; even using a distant tilt angle from the optimal angle the south zones are still better then some north zones using the optimal angle; the best panels tilt angles are the latitude angle ± 5 °C; the maximal AEsolar between the optimal tilt angle and the lower angle (20°) is of 92 kWh/year that represents a not problematic value. Then, it seems acceptable for a pitched roof south orientated (including also SW and SE) to mount the collectors close to the tilt roof angle. But it would be even better that architects designed the roof tilt angles to mach with the optimal panel tilt angle previous calculated. Finally, it must not forget that some additional cares must also be in weatherproof all penetrations through the roof covering with suitable flashings and purpose-made tiles.

Collector instantaneous efficiency n is defined as a ratio between the useful heat Q delivered and the hemispherical irradiance Gcol on the collector aperture Aa, according to (Rabl, 1985):

The hemispherical radiation Gcol reaching the collector aperture plane, to which the collector instantaneous efficiency is referred to, is calculated by the summation of the different components of radiation, for a given beam radiation incident angle в, and the plane tilt angle P, according to (Rabl, 1985):

Gcol =Icos6 + D(1 + cose)/2 + Rg (1 — cosy?)/2 (2)

where the ground reflected component — Rg = pgG — depends both on the global radiation G reaching the horizontal (ground) plane and on the ground reflectivity (albedo) pg.

As known, in the steady-state efficiency test (EN 12975-2; section 6.1) the collector efficiency curve is described by four parameters (considering a glazed collector): the optical efficiency n0, a global heat loss coefficient ai and (in the second order approach) a temperature dependent coefficient for the

2

global heat loss coefficient a2. The test includes also the measurement of incidence angle modifiers K(O) based on hemispherical irradiance, to be used in instantaneous power calculations.

In the quasi-dynamic efficiency test (EN 12975-2; section 6.3), the collector efficiency curve is described by five parameters (considering glazed collectors) and the incidence angle modifier values based on beam radiation. The five parameters are: the optical efficiency for beam radiation ц0Ь, the incidence angle modifier for diffuse radiation Kd, a global heat loss coefficient ci, a temperature dependent coefficient for the global heat loss coefficient c2 and a dynamic response coefficient c5 representing the effective heat capacity of the collector.

Besides the treatment of the dynamic response of the solar collector to temperature changes included in the quasi-dynamic test methodology, the major difference to the steady-state methodology lies in the decoupling of the radiation components, allowing the separation of effects affecting differently each of those components (e. g. optical effects, as referred by NEGST (2006) and Horta et al. (2008)).

According to EN 12975-2; section 6.1 the calculation of instantaneous collector power from steady — state efficiency curve parameters follows equation 3:

![]() Qss = nAO PcoA — a, (f — Ta ) — a2 (Tf — Ta ) Aa

Qss = nAO PcoA — a, (f — Ta ) — a2 (Tf — Ta ) Aa

whereas the same calculation using dynamic test efficiency curve parameters follows equation 4 [EN 12975-2; section 6.3]:

|

|

Horta et al. (2008) suggested a power correction methodology, applicable to power values determined after Eq.(3), accounting for the collector optical effects, affecting differently the radiation components which reach the absorber surface. According to this methodology, the power value is corrected using the following equation:

![]() ss_______

ss_______

1 — f (1 — KdfJ

where:

|

|||

|

|

||

is a diffuse radiation fraction to be suggested by the efficiency test laboratory after reference irradiation conditions for the collector test (Horta et al., 2008), and:

J Jні»,.в, )cos (O )sin (в )ів{ dOl

_п — л/

K = /2 /2_______________________

dif. h

J J cos(O )sin(O ‘)dOtdOl — П2 — П2

is a weighted average hemispherical incidence angle modifier (Carvalho et al, 2007), calculated after the longitudinal and transversal incident angle modifier (IAM) values measured in the steady state efficiency test. Since this correction applies to test results performed according to steady-state test method, the incidence angle modifier is based on hemispherical radiation.

3.1. Necessary steps

In order to implement the QD test methodology at LECS, three main aspects had to be dealt with:

a) Install an operational test circuit

The available test circuit was initially used for SS tests. It allows for the control of the collector inlet temperature at a constant value. Calibrated sensors were installed and a fixed stand for installation of the collectors was used. For measurement of irradiance on the collector aperture, two pyranometers were used, one with diffuse band for measurement of diffuse irradiance. Beam irradiance was calculated based on measurement of global and diffuse irradiance.

b) Develop a data acquisition programme

The data acquisition system was composed by a DMM equipment allowing reading of several sensors with voltage and resistance signals. A data acquisition program was developed using Visual Basic 6 language. The program’s purpose is to gather data from the measurement sensors, according to the methodology set out in the standard [1]. The measured data is recorded on a file with the collector name, test date and ORI extension. Files with ORI extension contain sensors readings in volts and ohms. The information on sensor readings is supplemented by information such as the date and time (hour, minute, second) and reading number.

The acquisition program also calculates physical values using the calibration parameters of each sensor and records them on a file with the collector name, test date and TPO extension.

The time step for data acquisition is 5 s, which is in agreement with the suggestions given in the standard.

c) Develop a tool for parameter identification

The software chosen for the development of the tool for parameter identification is Mathlab. With this software a pre-processing of the data collected with the data acquisition programme is also performed. This pre-processing generates files with mean values of relevant data for five minutes intervals. Generation of graphic for analyses of the data collected according to the recommendations of the standard is also performed. Example of these graphs can be seen in section

4., Fig. 1 of this work. This tool also includes a multilinear analyses of the data collected, in order to determine the characteristic parameters according to equation (4).

3.2. Multilinear regression

The following (conventional) multiple linear regression model describes a relationship between the k independent variables, xj, and the dependent variable Y

Y = Д) + Ax1 + Ax24 + Pa + є-> (6)

This model was applied to equation (4), heat balance equation for QD test method, for determination of the collector characteristic parameters (5). Since the parameter IAM for beam radiation, Keb(0), is dependent on the incidence angle, 0, an assumption for its functional form is needed. In a first approach this dependence was considered to be given by;

![]() Keb(0)= 1 — b0(— -1 I cos 0

Keb(0)= 1 — b0(— -1 I cos 0

|

|

and equation (4) could be re-written as:

Characteristic parameters: Pi= F(xa)en ;p2= F(xa)enb0; p3= F(xa)enK0d ;p4=d; p5=c2; p6=c5

A programme was developed for determination of the characteristic parameters based on the measured data (5 minute average values).

The same programme also produces graphs for analyses of data variability, according to the EN 12975-2; section 6.3. These graphs are:

• Difference between mean fluid temperature and ambient temperature versus global irradiance;

• Beam versus global irradiance;

• Beam irradiance versus incidence angle;

Based on the calculated parameters and measured values, it calculates the power delivered by the collector using the collector heat balance model of equation (8) and represents it graphically for comparison with the measured power delivered by the collector during the test sequences.

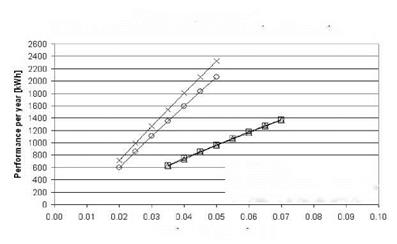

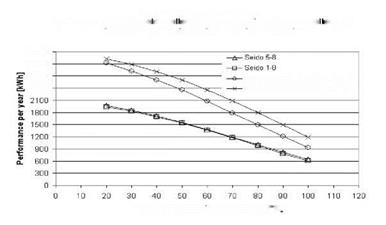

Calculations with different glass tube radius are carried out. Other parameters are here changed as well: For the collectors with the curved absorbers, the glass tube centre distance and the radius of the absorber fins are changed as well. For the collectors with the flat fins the glass tube centre distance and the width of the fins are changed as well. For Seido 5-8 and 1-8 the radius of the glass tubes is varied from 0.035 m to 0.070 m. For Seido 10-20 with curved and flat absorbers the glass radius is varied from 0.02 m to 0.05 m. The thermal performance is shown as a function of the glass tube radius for

|

|

Copenhagen the glass tube radius almost does not influence the optimum collector tilt. The change in the optimum orientation follows the same tendency as seen with a change in the other parameters. The collectors in Nuussuaq should be turned more towards east. In Sisimiut the collectors with the curved absorbers should be turned slightly from south towards west, and the collectors with flat absorbers should be turned 35° from south towards west. In Copenhagen the change in the orientation is only about 2° more from south towards west. In Fig 7 the thermal performance of the collectors in

Copenhagen the glass tube radius almost does not influence the optimum collector tilt. The change in the optimum orientation follows the same tendency as seen with a change in the other parameters. The collectors in Nuussuaq should be turned more towards east. In Sisimiut the collectors with the curved absorbers should be turned slightly from south towards west, and the collectors with flat absorbers should be turned 35° from south towards west. In Copenhagen the change in the orientation is only about 2° more from south towards west. In Fig 7 the thermal performance of the collectors in

|

|

Nuussuaq is shown with an increased tube radius for all the collectors.

Mean collector fluid temperature [ Cl

Fig 7. Improvement of the thermal performance as a result of an increase

in tube radius in Nuussuaq.

The last simulations were done with the models using the improved centre distance, larger strip angle and width and larger transmittance-absorptance product. The thermal performance of the improved

collectors in Nuussuaq in seen in Fig 8. The overall improvement of the collectors results in an increase in thermal performance of up to 9 % with a mean collector fluid temperature of 60 ° for the collectors in Nuussuaq. For Sisimiut the improvement of the collectors is about 5 % for a mean collector fluid temperature of 60 °C. In Copenhagen the least overall improvement is detected. The highest improvement is in Copenhagen seen for Seido 10-20 with flat absorbers.

[1] L. J. Shah, S. Furbo, (2005). Theoretical investigations of differently designed heatpie evacuated tubular collectors, Denmark.

[2] L. J. Shah, S. Furbo (2005). Utilization of solar radiation at high latitudes with evacuated tubular collectors, Denmark.

[3] J. Fan, J. Dragsted, Rikke Jorgensen, S. Furbo (2006). B^redygtigt arktisk byggeri i det 21. arhundrede, Denmark.

[4] J. Fan, J. Dragsted, S. Furbo (2007). Validation of simulation models for differently designed heat-pipe evacuated tubular collectors, Denmark.

In order to determine the efficiency parameters of solar thermal collectors according to ISO 9806 or EN 12975, two different procedures can be used: the steady state test method and the quasi dynamic test method.

During the steady state test, all boundary conditions such as solar radiance, ambient temperature and collector inlet temperature must be constant. After recording data points over a representative range of operating conditions, the collector efficiency curve can be determined by means of multilinear regression using the least square method.

During the quasi dynamic test the boundary conditions must vary. Based on a series of measurements, specific collector parameters are determined, as well. With the quasi dynamic test method, additional parameters such as the heat capacity of the collector and the incident angle modifier coefficient can be determined in addition to the efficiency curve.

1.1. Case-study buildings

Two case study buildings were considered. Case-study 1 is a T1 apartment (with one bedroom) located in the ground floor of a 6-floor apartment building [4]. The second case-study is a T3 detached dwelling (three bedrooms). Table 2 presents for each the main characteristics influencing their thermal behaviour.

1.2. Climatic regions / locations analysed

As stated in the introduction, one of the aims of this study is to understand the influence of the climate in the resultant energy label, and what levels of envelope and equipment sophistication are needed to cope with the climate (first to fulfil the regulation and then to reach class A+) in each of the locations. To this purpose, a selection of locations was made in an attempt to represent the

diversity of climate of mainland Portugal. The locations selected were: Lisboa, Faro, Guarda, Penhas Douradas, Evora, Viana do Castelo and Bragan? a.

Table 3 shows the main characteristics of each zone in order to understand the difference between them.

In order to remove trade barriers inside Europe and to support the establishment of a uniform European market the European standardisation bodies CEN and CENELEC[4] created a uniform methodology for the marking of products on the basis of European standards. The mark resulting from this approach is the so-called Keymark which aims to be accepted all over Europe (see Figure 2). For solar thermal products the corresponding label is named Solar Keymark.

In order to remove trade barriers inside Europe and to support the establishment of a uniform European market the European standardisation bodies CEN and CENELEC[4] created a uniform methodology for the marking of products on the basis of European standards. The mark resulting from this approach is the so-called Keymark which aims to be accepted all over Europe (see Figure 2). For solar thermal products the corresponding label is named Solar Keymark.

The Solar Keymark is a voluntary third-party certification mark. By obtaining the Solar Keymark, the solar product qualifies for nearly all the different European member state regulatory and financial incentive schemes.

The elaboration of the specific Solar Keymark scheme rules /5/ which provides the basis for Solar Keymark certification started at the beginning of 2000 within the framework of a European project initiated by the European Solar Thermal Industry Federation, ESTIF and co-financed by the European Commission. At the beginning of 2003 the final version of the Solar Keymark scheme rules were published. During the years 2006 and 2007 these scheme rules were revised within an other European project. In both projects representatives from the solar thermal industry, the leading solar thermal test institutions and certifications bodies co-operated.

The Solar Keymark for solar collectors requires that the products fulfil the requirements stated in the European Standard EN 12975-1 and are tested according to EN 12975-2.

In order to certify factory made solar thermal systems according to the Solar Keymark scheme rules they must be in line with the requirements of EN 12976-1 and must be tested according to EN 12976-2.

In order to obtain the Solar Keymark the following three major steps are required:

• Picking of random test samples from the factory production or the manufacturer’s stock by an accepted inspector.

• Successful type testing of the solar collectors or systems respectively by an accredited test lab

• Inspection of the manufacturer’s quality management system

If all the requirements mentioned above are fulfilled the Solar Keymark certification can be issued by certification bodies empowered by CEN Certification Board.

Modern selective absorber coatings usually are thin layer systems on metal substrates which selectively absorb short wavelength photons — a process which is enhanced by multiple scattering at small metal particles in a dielectric matrix (so-called Cermet layers). Long wavelengths average over the particle mix and do not resolve the particles of typical size (order of magnitude is 10nm). They experience an effective medium formed by the metal-dieelectric mixture. Interference effects are being used to maximize reflectance in the infrared range. Therefore the exact thickness, the volume fraction of the metal content of layers and the size of particles determines the optical and thermal performance — solar absorptivity and thermal emissivity. The high-temperatures as reached in concentrating collectors during operation on the other hand tend to increase the mobility of atoms in the layers. Therefore interdiffusion might deteriorate simple layer systems. Additional barrier layers therefore are used to restrict mobility. In some cases adhesive layers can improve the bonding stability of the system.

|

time in h Figure 2: Change of absorptivity and emissivity of prototype coating |

Within the project Fresnel-II Fraunhofer ISE developed a sputtered air-stable absorber coating on stainless steel that resists temperatures up to 450°C. When heated at 500°C after a relaxation time the coating did not change the properties even after weeks of heating. The obtained solar absorptivity is 94% (AM1.5 global) with an emissivity of 18% in respect of a black radiator at 450°C. The application of such a coating is the single-tube absorber of a Linear Fresnel Collector. Of course, other applications are conceivable.

Other thin layer systems can be used to produce mirror coatings for secondary concentrators. These mirrors have to withstand elevated temperatures due to the proximity to the absorber tube. The solar reflectance shall be high, therefore first surface mirrors were the aim of the project. On the basis of highly reflecting silver an optical layer system has been developed and improved. Again barrier and adhesion properties have to be taken into account. Also mirror coatings change their properties slightly upon heating. It could be shown that the reflectivity changes ceased after a few hours when being heated at 150°C and 250°C (which seems to be sufficient for a secondary reflector in a linear Fresnel collector), but not at 350°C. Therefore the application e. g. for tower receivers seems to be problematic. Further work is needed to develop mirror coatings which are stable at even higher temperature loads.

|

Figure 3: Change of solar reflectance (AM1.5 global) for first surface mirror due to heating at different temperatures |

The durability and resistance against several environmental factors, not only temperature but also UV, humidity, salt and air pollution, is a main concern with regard to the cost effectiveness of solar technologies. Large investments are needed in order to harvest the sun at nearly no cost. Longevity, performance and cost have to be considered in parallel. Innovative complex and possibly expensive new components cannot to be cost effective if their performance degrades after short time. However, cheap products might be replaced when disassembly and replacement can be standardized.

In climatic chambers and similarly in outdoor exposition components can be checked and qualified. Certainly unsuitable materials can be excluded. Relative comparisons between various development options are possible. However it is not trivial to translate results from accelerated indoor testing (using higher loads than experienced in reality) to a quantitative lifetime estimation. Comparisons with actual outdoor weathering need very long time and are not available for new products. Thus risk can only be minimized by understanding the material degradation processes and the real load factors during application. Combining this material and process specific knowledge with carefully designed accelerated indoor tests at least can minimize the risk of failure.

A CPC collector having an aperture area of 1.87 m2 was analysed. The collector uses a circular absorber tube with an outer diameter of 19 mm. With an aperture width of 103 mm this results in a concentration ratio of C = 1.73.

Table 1 shows the results determined with the tests under quasi-dynamic and steady state conditions. The mean diffuse fraction during the test under steady state conditions was D = 0.3.

Figure 3 shows the power curves calculated using the collector parameters determined under quasidynamic conditions for diffuse fractions of 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 together with the power curve calculated with the collector parameters determined under steady state conditions.

|

Table 1. Collector parameters determined

|

|

Figure 3 shows the significant dependency of the collector output on the diffuse fraction D. For a diffuse fraction of D = 0.5 the maximum collector output is reduced by 160 W/m2 and 11 % respectively compared to the collector output at a diffuse fraction of D = 0.1.

|

— •-D = 0.1 ………. D = 0.3 ——— D = 0.5 steady state

Fig. 3. Power curves (G = 1000 W/m2) for different diffuse fractions and under steady state conditions

The power curve determined using the test method under steady state conditions shows a similar appearance as the power curve determined for a diffuse fraction of D = 0.3. This attributes to the fact that the mean diffuse fraction during the test under steady state conditions has been D = 0.3.

From the presented investigation two main conclusions can be drawn:

1. The collector parameters gained from the test under quasi-dynamic conditions are very well suited to calculate the collector performance for different diffuse fractions. 2

The test method under quasi-dynamic conditions is, contrary to the test method under steady state conditions, very well suited to determine the thermal performance of CPC collectors having a concentration ratio larger than 1. Especially the differentiation between diffuse and beam irradiance permits a reliable modelling of the thermal performance under arbitrarily diffuse fractions. The level of detail provides a more exact estimation of the yearly energy gain and thus a better planning reliability during the dimensioning of solar thermal systems using CPC collectors.

Due to the poor reproduction of the incident irradiance the test method under steady state conditions is not suited for CPC collectors. The inaccuracy of the test method even grows with rising concentration factors.

The increasing efforts in the fields of solar thermal process heat and solar cooling have led to a rising number of concentrating collectors on the European market. Against this background it is appropriate to nominate the test method under quasi-dynamic conditions as the sole test method to be used for concentrating collectors within the next revision of the European standard EN 12975.

|

a1 |

[W/(m2K)] |

Heat loss coefficient |

|

a2 |

[W/(m2K2)] |

Temperature dependent heat loss coefficient |

|

A |

[m2] |

Aperture area |

|

C |

[-] |

Concentration ratio |

|

ceff |

[J/(m2K)] |

Effective heat capacity of the collector |

|

D |

[-] |

Diffuse fraction |

|

G |

[W/m2] |

Hemispherical irradiance |

|

Gdfu |

[W/m2] |

Diffuse irradiance |

|

Gdir |

[W/m2] |

Beam irradiance |

|

Gnet |

[W/m2] |

Useful irradiance |

|

K(0) |

[-] |

Incidence angle modifier for hemispherical irradiance |

|

Kbeam(0) |

[-] |

Incidence angle modifier for beam irradiance |

|

Kdfu |

[-] |

Incidence angle modifier for diffuse irradiance |

|

N |

[-] |

Fraction of useful irradiance |

|

Q |

[W] |

Collector output |

|

П0 |

[-] |

Conversion factor |

|

0 |

[-] |

Angle of incidence |

|

0a |

[°C] |

Ambient temperature |

|

0fl, m |

[°C] |

Mean fluid temperature |

|

t |

[s] |

Time |

[1] DIN EN 12975-2:2006, Thermal solar systems and components — Solar collectors — Part 2: Test methods -, 2006.